Welcome to

Ngorongoro Conservation Area

The stunning beauty of the Ngorongoro Crater is beyond words. Standing at the viewpoint, gazing out over the vast expanse, you’ll see clouds gently resting along the rim and feel the cool mountain breeze brushing against your skin. In that moment, the magnificence of nature’s creation becomes undeniably clear. The stunning beauty of the Ngorongoro Crater is beyond words. Standing at the viewpoint, gazing out over the vast expanse, you’ll see clouds gently resting along the rim and feel the cool mountain breeze brushing against your skin. In that moment, the magnificence of nature’s creation becomes undeniably clear.

Overview

The Ngorongoro Crater, towered alongside Mount Kilimanjaro nearly three million years ago, stands as one of the highest peaks in Africa. Formed during the tumultuous creation of the Rift Valley, its volcanic summit erupted when early humans began to roam the surrounding plains.

The Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA) covers 8,292 sq km. It boasts the finest blend of landscapes, wildlife, people and archaeological sites in Africa. It is also a pioneering experiment in multiple land use, which involves conservation without complete absenteeism of human interference.

Geology

The landscape of the Ngorongoro Crater has been shaped by rifts and volcanic activity. A rift occurs when the Earth’s crust experiences a disturbance, causing its edges to either rise or sink. These shifts often allow molten rock, or lava, to reach the surface, where it solidifies. When lava continues to flow from the same opening over an extended period, its accumulation ends up forming a volcano.

In the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, significant rifts are located north of Lake Eyasi and east of Lakes Manyara and Natron. Over the past four million years, these areas gave rise to the nine volcanoes of the Ngorongoro highlands. Among them, only Oldonyo Lengai remains active. Ash and dust from its eruptions were carried by the wind, enriching the Serengeti plains with fertile soils.

Ngorongoro Wildlife

Today, Ngorongoro’s caldera shelters the most beautiful wildlife on earth. The rich pasture and permanent water of the Crater floor supports a resident population of some 20,000 to 25,000 large mammals. Even though they are not confined by the crater walls and can leave freely, they stay due to its favorable conditions.

The Ngorongoro Crater is very important in terms of biodiversity conservation, as it is home to numerous endangered species. Moreover, its wildlife density is high, achieving the highest known population record of lions.

The grassy expanse of the Crater floor is home to a wide variety of grazing animals, including wildebeest, zebras, gazelles, buffalo, elands, hartebeests, and warthogs. Swamps and forests complement this ecosystem, offering habitats for hippos, some of Tanzania’s last black rhinos, elephants with massive tusks, waterbucks, reedbucks, bushbucks, baboons, and vervet monkeys.

The steep inner slopes provide shelter for species like dik-diks and the rare mountain reedbuck. Towering euphorbias cling to the crater walls, while Fever and Fig trees forests on the crater floor offer shade to a remarkable array of wildlife. These animals, in turn, sustain a thriving population of predators such as lions and leopards, along with scavengers like hyenas and jackals.

Ngorongoro is also part of the Great Migration. Every year, over a million wildebeest go through the Serengeti ecosystem as part of their annual migration, reaching spots of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area like lake Ndutu, where they calve their offsprings. This is the perfect setting for an authentic natural spectacle.

Birdlife

The birdlife in the Ngorongoro Crater varies significantly with the seasons, as it is home to both resident and migratory species. Year-round residents include ostriches, bustards, and plovers, which can be spotted no matter the time of year. During the wet season, they are joined by European migrants such as white storks, yellow wagtails, and swallows, which arrive from November to May, aligning with Africa’s rains and the winter months in Eurasia.

Local migrants, including flamingos, storks, and ducks, also frequent the crater, but the condition of the lakes and ponds dictates their presence. Other bird species commonly seen are stonechats, anteater chats, Shalow’s wheatears, and fiscal shrikes. Raptors like augur buzzards and Verreaux’s eagles are permanent residents, adding to the diversity of the avian population. In total, the Crater hosts over 500 bird species, making it a paradise for bird enthusiasts.

Climate of Ngorongoro Crater

Ngorongoro safari lodges are situated along the crater rim, which is 2,235 metres (7,264 feet) above sea level. It can get quite fresh up here and gets very cold at night in the winter months of June to August. Meanwhile, daytime temperatures in the crater itself can become quite warm, offering a striking contrast to the crisp air above.

Dry Season

The weather is usually dry from June to November. July is the coldest month and highland temperatures may fall below freezing. Although there is a lot of sunshine on the crater floor, the rim can sometimes be covered in mist or even freeze at night.

Rainy Season

It rains anytime from November to May. The amount and pattern of rainfall varies and a dry period in January and February may split the rainy season into short (November and December) and long rains (from March to May). The forested eastern slopes get much more rain due to their elevation than the arid country to the west. The rain arrives in stormy showers usually during afternoons and nights, cleansing the air to reveal clear views. Although it gets warmer when compared to the Dry Season, mornings are still cold, and even during the long rains, temperatures could drop due to cold fronts.

The Ngorongoro Crater Floor

Exploring the emerald plains and forests of the Ngorongoro Crater floor through interpretive game drives fosters a deep appreciation for the region’s wildlife and local communities.

A steep dirt road descends from the Malanja Depression on the crater rim to the Bgiribgiri crater floor. At the top, Maasai women and children often welcome visitors and allow photographs for a small fee. The Malanja Depression is an open, grassy area ideal for spotting highland antelope species like mountain reedbuck and Kirk’s dik-dik, along with birds such as the striking augur buzzard and Schalow’s wheatear.

The crater floor’s centerpiece is Lake Magadi, a shallow soda lake that attracts large flocks of flamingos. Most of the floor is open grassland, making it an excellent area for wildlife viewing. Common sightings include black rhino, lions, hyenas, gazelles, wildebeests, and zebras. The hippo pool near Mandusi Swamp is a favorite picnic spot, offering a chance to relax while surrounded by the park’s breathtaking scenery.

Highlights and FAQ

Ngorongoro -> Arusha: ~ 3h drive

Ngorongoro -> Serengeti: ~2h drive

Ngorongoro -> Tarangire ~2h drive

Ngorongoro -> Lake Manyara: ~1h drive

Area: 8.292 km²

Travel: 180 km from Arusha

Established: 1959

Visitors: 580.000 / year

Official Homepage

- All of the Big Five (Lion, Rhino, African Buffalo, Elephant, Leopard)

- Hippos

- Gnus

- Grant & Thomson gazelles

- Zebras

- Jackals

- African wild dog

- Ostriches

- Crater Game Drive

- Olduvai Gorge Visit (Ancient humanoid fossils)

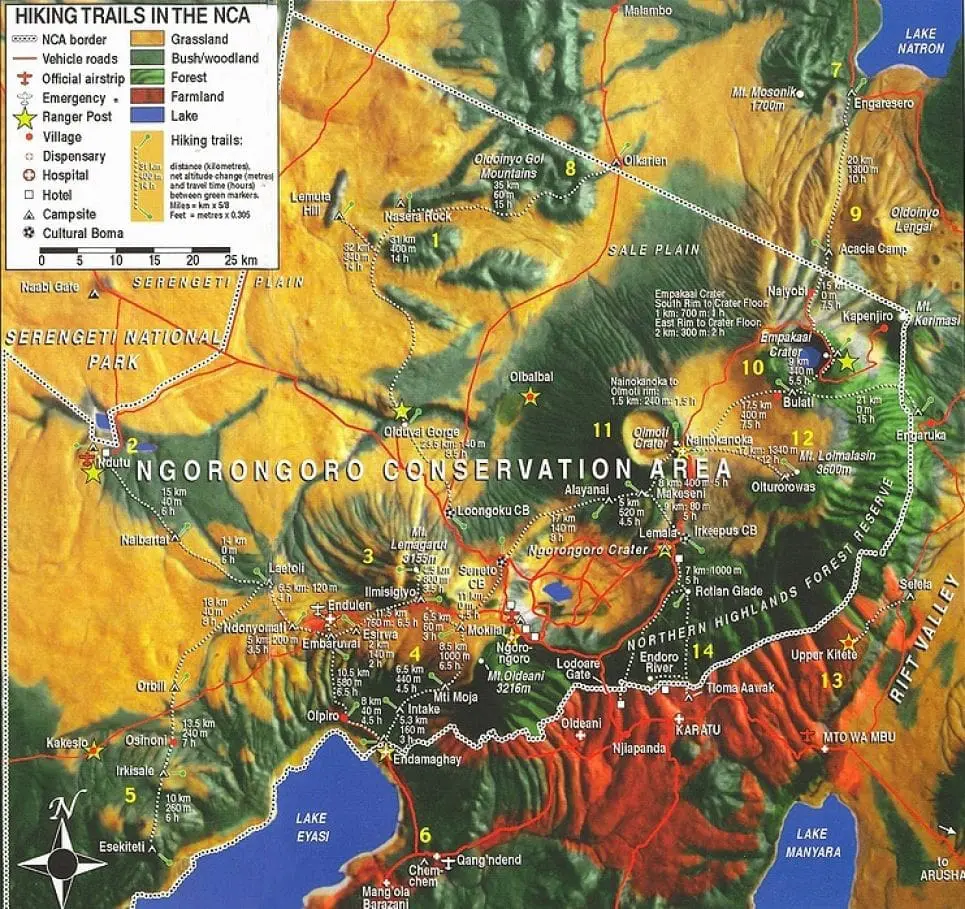

- Forest Hikes

- Maasai Village visit